OM1 - How do gravity assists/slingshots work?

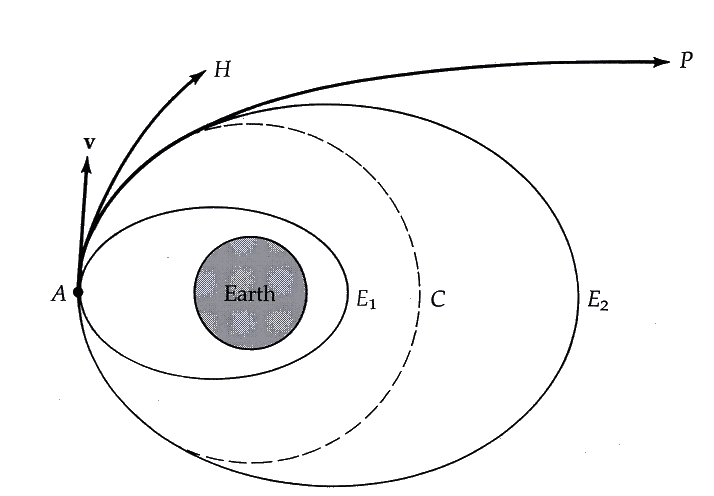

Assume we are placed at a certain height \(r_p\) above the Earth, well outside the atmosphere. Give ourselves a velocity \(\vec v_0\) orthogonal to the Earth-us ray vector. Assume the Earth was spherical and homogeneous, the Sun's effect were negligible and that there was no moon (how's that for simplification?). Then we know from Kepler that our possible trajectories are conic sections (ellipses, parabolas, or hyperbolas) with a focus on the Earth. We also know that our velocity is tangent to our trajectory (from standard kinematics). However, there are multiple conic sections with a focus on the Earth, passing through our current position and tangent to our velocity, as the following diagram shows:

Exactly which conic section we'll follow by coasting in Earth's gravity is dependent on the modulus of our initial velocity. Namely, if \(v_0\) was equal to the velocity needed for a circular orbit (which is \(\sqrt{\frac{GM_\oplus}{r_p} }\)) the orbit would be obviously a circle; if it was slightly more, the orbit would start to get elliptical.

In the elliptical case, our starting position is the closest approach to Earth (the perigee) and antipodally we would find a farthest point, the apogee, where again the velocity is orthogonal to the radius vector.

If however we overcome a certain threshold velocity (the escape velocity for this situation) the orbit "opens up" and becomes hyperbolic. An hyperbolic orbit is unbound and not periodic: we escape the Earth system.

At exactly the threshold we obtain the curious boundary case of parabolic orbits, which we are not interested in right now.

What happens instead if we have instead \(v_0\) less than the circular orbit velocity? Then our orbit is still an ellipse, but the point opposite from us is closer to Earth than we are right now, so we are actually at the apogee and that other one is the perigee.

We are mainly interested in hyperbolic orbits.

A useful parameter for classifying orbits is the total specific mechanical energy

\[E/m =: \epsilon = \epsilon_K + \epsilon_G = \frac{1}{2} v^2 - \frac{GM_\oplus}{r} \]

which is conserved along the orbit. Singularly, the kinetic and gravitational components are not conserved, but their sum is. When our spacecraft gets farther and closer to Earth, it's exchanging its total conserved energy back and forth between kinetic and gravitational.

If \(\epsilon<0\) the orbit is bound, so it's an ellipse/circle. Since \(\epsilon_K \geq 0\) (because it's a square), then

\[\epsilon_K \geq 0 \Rightarrow \epsilon - \epsilon_G \Rightarrow \epsilon + \frac{GM}{r} \geq 0 \]

\[\Rightarrow r \leq \frac{GM_\oplus}{-\epsilon}\]

and so there is a maximum radius \(r_a = \frac{GM_\oplus}{|\epsilon|}\). Intuitively, the spacecraft does not have enough energy to escape the gravitational well, and it's stuck inside a particular sphere centered on the primary.

Instead if \(\epsilon>0\) the orbit is unbound. The spacecraft can "reach infinity" with energy to spare. With this I mean that, when \(r\rightarrow \infty\):

\[\epsilon = \frac{1}{2} v_\infty^2 - \frac{GM_\oplus}{\infty} \sim \frac{1}{2}v_\infty^2\]

\[ \Rightarrow v_\infty = \sqrt{2\epsilon}\]

so the spacecraft leaves the Earth system with a nonzero velocity \(v_\infty\), or better said, as the spacecraft gets farther and farther from Earth, it's velocity approaches a constant.

The full trajectory has the spacecraft approach Earth from infinity with an initial velocity \(\vec v_i\) with norm \(|\vec v_i| = v_\infty\), as we've proven, then following the hyperbolic trajectory accelerating up to a maximum speed \(v_0\) at the perigee, then slowing down as it exits the system and approaching the final velocity \(\vec v_f\) with, again, norm \(|\vec v_f| = v_\infty\). This speed must be equal to the initial speed because energy is conserved.

We have by the way derived an interesting fact: in this single-planet approximation, it does not matter how slowly you approach the planet. There is no way you can get into orbit like this. As little as your \(\vec v_i\) of approach is, you still have positive energy \(\epsilon = |v_i|^2/2\), and this is conserved along the fly-by. You just reach a periapsis (apsis instead of gee is agnostic about the primary), at which your speed is maximum (it's actually slightly larger than the escape velocity) and then you are swung outside the reach of the planet, again slowing down to speed \(|\vec v_i|\). (Or you can crash on the surface. That's an option.). So one must make up some plan if one wants to visit a planet and enter orbit. The most simple is just to use thrusters to slow down at periapsis; this moves you from the hyperbolic orbit to an elliptical orbit, but requires quite some fuel - at least the \(\Delta v\) to kill \(v_\infty\). There are however, surprisingly, effortless ways, but not in this approximation; we'll talk about them later.

The two velocities \(\vec v_i\) and \(\vec v_f\) have the same modulus but not necessarily the same direction. This means the encounter with the planet has managed to change the direction of our course. In particular, it has given us a change in velocity

\[ \Delta \vec v = \vec v_f - \vec v_i \]

corresponding to a change in momentum, or an impulse

\[\Delta \vec p = m \Delta \vec v\]

Note that our momentum is not conserved. We have exchanged momentum with the planet, which however was barely affected by our donation. So, in the absolutely plausible approximation where planets are "on tracks", way too massive to be affected by spacecraft, the theory of spacecraft or small objects moving around in the gravitational potential of the sun and planets does not conserve momentum. In fact, it does not even conserve energy in general! However, in the particular case of a spacecraft in the gravitational field of a single stationary planet, energy is conserved.

Energy conservation is connected to the time-independence of the gravitational potential \(V(r)\). In fact, the Newtonian potential from a planet stationary at the origin \(-\frac{GM_\oplus}{r}\) is independent of time. But if the planet moves, for example, one has

\[V = - \frac{GM_\oplus}{|\vec r - \vec r_\oplus(t)|}\]

and so \(V\) is both a function of spacecraft position \(r\) and time \(t\), through the position of the planet. In general, if there are multiple astronomical bodies involved, it's pretty unlikely they'd just stand there; typically they would set into orbits themselves. Then when studying the dynamics of a spacecraft coasting in such a landscape we would certainly recognize violations of conservation of the momentum and energy of the spacecraft, as these quantitites are exchanged with the astronomical bodies.

Now, let's take a look at our hyperbolic encounter from another perspective. Let's zoom back:

you can actually hear the 'thump' sound

That's interesting. It looks like the spacecraft has bounced on the planet. In fact it acted precisely like a ball bouncing on another, very massive, ball in an elastic collision would. This is why a fly-by or an encounter can also be seen as an elastic collison or an elastic scattering. Basically by zooming out we've discarded all (for now) superfluous information on the specific hour-by-hour details of the encounter and reduced ourselves to the relevant information over the course of months: the spacecraft approaches the planet with constant velocity \(\vec v_i\), interacts with the planet at a discrete event where it's given a change in velocity \(\Delta \vec v\), and exits with constant velocity \(\vec v_f\).

Note that we've gotten a \(\Delta \vec v\), but not a \(\Delta v\), which is what we are interested in in space travel. To tackle this we zoom out a little more, until the Sun comes into the stage.

Until now we've neglected the gravitational field of the Sun. People might tell you that whenever you're close to the Earth, the gravitational field of the Sun is negligible compared to the Earth's, and therefore might be ignored.

This is not always true, moreover it's not the reason we can ignore the Sun's field.

In fact, this is false exactly for our only natural satellite. The gravitational accelerations experienced by the Moon due to the Earth and Sun are (\(L\) stands for Moon because I don't have astronomical symbols in Mathjax):

\[g_\oplus = \frac{GM_\oplus}{R_{\oplus L}^2} \sim 0.0027 \, \text{m}/\text{s}^2\] \[g_\odot = \frac{GM_\odot}{R_{\odot L}^2} \sim 0.0059 \, \text{m}/\text{s}^2\]

So the gravitational field of the Sun is stronger than that of the Earth on the Moon. So then, why isn't the Moon escaping the tiranny of the Earth and leaving to become an independent planet, or at the very least not acting erratically?

The solution is that we're analizing this situation from the Earth, that is, in the reference frame where the Earth is stationary. But the Earth itself orbits the Sun, pulled by the same gravitational field. The reference frame of the Earth corotates with the Earth around the Sun, and therefore is not inertial and features a centrifugal force that cancels exactly the Sun's field (see CM1).

While they cancel perfectly on the Earth, they don't exactly match when you move away from it (centrifugal force goes as \(\sim r\), gravitational as \(r^{-2}\)), so when the Moon moves closer and farther to the Sun in its orbit, it feels the little force that it's the difference of the Sun-gravitational and centrifugal forces, which is very small compared to the Earth's pull. This is why one talks of the (small) perturbation to the Moon's orbit due to the Sun.

What we've sketched is a consequence of the Equivalence Principle, which by the way you should look up if you are interested in general relativity.

So, everything is cool and all in the Earth's frame, but our probe exits and enters the Earth's sphere of influence, which in our zoomed-back perspective is pretty small. The Earth's frame is pretty unwieldy for most of our trip, happening in the Sun's domain. So let's switch to the Sun's reference frame.

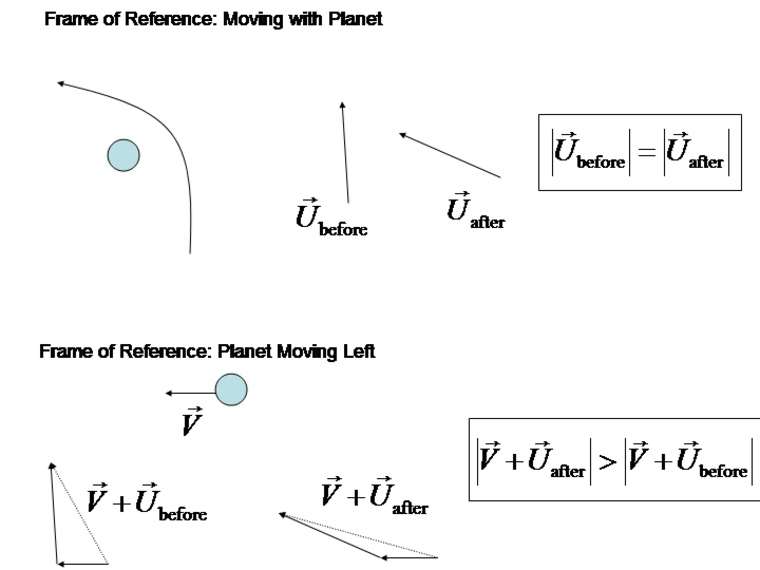

The Earth orbits the Sun in a mostly circular orbit at a velocity \(\vec v_\oplus\), with speed \(v_\oplus \sim 30 \mathrm{km}/\mathrm{s}\) (that's pretty high). Our in and out velocities in the Sun frame are:

\[ \vec v'_i = \vec v_i + \vec v_\oplus \quad \vec v'_f = \vec v_f + \vec v_\oplus \]

and note that the new norms of the in/out velocities do not necessarily have to be equal:

\[ | \vec v_i'| \neq |\vec v_f'|\]

which is precisely the \(\Delta v\) we wanted. In the Sun frame, we can gain or lose velocity (and therefore energy) by "bouncing" on planets, in effect having close encounters.

To understand the reasoning behind this apparently free lunch, consider as an analogy the simple case of a ball bouncing on a stationary, infinitely stiff and massive wall. By bouncing elastically on the wall, the ball only changes the direction of its speed, not the magnitude, so it cannot extract energy from the wall (but it can change its momentum).

However, changing reference frame, the wall is moving. When the ball and wall hit, the wall can impart energy to the ball.

Similarly, planets moved in orbit around the sun can be seen as practically unlimited reservoirs of energy and momentum. A small spacecraft can "bounce" elastically on a planet and extract/lose energy.